This piece first appeared on www.livemint.com on 8th March 2016.

Consider the culinary scenario in India today. Opening value-for-money, concept restaurants is now the norm, not the exception. There’s a refreshing new focus on Indian food, and local sustainable eateries are gaining momentum. Pay scales in restaurants and hotels are also far better than they were even a decade ago. In short, there has never been a better time to be a chef in this country. Well, a male chef at least.

That is still one major conundrum which plagues the hospitality industry in India: The huge gender disparity in the kitchen and, more importantly, how we treat the ones that do manage to be a part of these hallowed portals.

With just seven years of professional cooking experience, I’m pretty much a newbie in this line of work. I love being a chef and I thrive on the highs (and lows) of restaurant life. But this gender imbalance is the one thing I just cannot wrap my head around.

The fact that we are pleasantly surprised every time we see a woman cook behind the pass is telling. With the exception of a few prominent chefs—Ritu Dalmia, Madhu Krishnan to name two—women in restaurants and hotels are largely confined to front of the house. Which is surprising, especially in a cultural context that has always considered mothers and grandmothers to be “the best cooks in the world”.

Why then is the female representation in this industry so low? Attempting to answer this is akin to figuring out why a nation of 1.25 billion people cannot come up with an 11-member team worthy of qualifying for the football World Cup.

The obvious crux of the problem lies within the kitchen itself. It’s a tough line of work and demands immense passion and dedication of anyone choosing this career path. It also means a substantial commitment of time and energy; and, consequently, de-prioritizing family life. The fact that sexism and sometimes, even misogyny, are still very much an intrinsic part of the restaurant culture only compounds the problem. Society has classified the restaurant kitchen to be a high-testosterone environment that encourages boisterous, abusive behaviour, where women “have no place”. Girls, therefore, are strongly discouraged even from applying to hotel management institutes.

Nevertheless, as in every male-dominated field (and, make no mistake, they are all male dominated) in India, thousands of women still do enter this industry with a passion to succeed and excel. As they mature, however, their environment pulls them down, family pressures takes their toll, and survival needs take over. This has a domino effect on younger aspirants, dampening their enthusiasm for the field, and giving their critics another handle. In short, the factors behind the woefully small presence of women in the professional kitchen are no different from the factors that keep them back in other challenging fields.

It may be premature to be optimistic about something that’s so deeply ingrained in our society but I do think we are making a difference in our own way at The Bombay Canteen. We have nine women in our kitchen team, almost a third of our total strength and I’m unabashedly proud of the fact. Most of them are line cooks, while others are trainees from hotel management institutes. There are even a few from other fields of work testing waters in our kitchen with dreams of a career change. This would’ve seemed absurd say, 10 years ago, but today it’s possible. A good sign.

For women—and men—seeking a career in the kitchen, there’s also a new brigade of young female chefs and restaurateurs such as Pooja Dhingra, Gauri Devidayal, Naina de Bois-Juzan, Karishma Dalal, Anahita N Dhondy and Sanjana Patel who have carved a niche for themselves in India. We need more and more such women who fight the stereotype and emerge as role-models for young people considering this line of work.

I think the onus is also on industry leaders—chefs, restaurateurs, hoteliers and hotel management professors—to provide women a platform that will reinstate their faith in this career.

For a good many years after its launch in 1994, the ITC chain of hotels had its West View restaurant brand run solely by women. They have since changed their women-only policy. Only two West View restaurants remain in the country, one in New Delhi and the other in Kolkata. When I called to enquire, I was informed that there were now only two or three women working in each of the outlets.

While a fantastic initiative, I think such extreme steps could end up being counter-productive. What would be far more conducive to encouraging equality in the professional kitchen is a more equitable work environment.

First and foremost, it is important for male cooks—who may never have worked with women before—to understand what women need, to respect boundaries and get accustomed to female co-workers. Being surrounded by men for 10-12 hours a day can be overwhelming and small gestures, such as respect for their personal space, can go a long way.

Policies regarding abuse, be it physical or verbal, need to be not only adopted but also strictly enforced. Superiors need to be approachable and accommodating, whenever possible, especially with regard to shift timings and travel arrangements (think going home alone at night through unsafe neighborhoods). It is equally imperative for women to know they don’t need to “man up” in the kitchen; but only to pull their weight to win their male colleagues’ respect.

Empathy in a kitchen is a valuable trait. Nearly a year ago, not long after The Bombay Canteen opened, I noticed one of the woman cooks struggling to reach her station’s assigned shelf in the walk-in cooler. It may seem comical in hindsight, but shifting her mise-en-place to a lower shelf was a simple yet rather impactful step, one that I could very easily have missed.

A kitchen dominated by male cooks is boring and monochromatic. Women bring in a whole new dimension to the table. This is not to say that they cook better or worse than their male counterparts—just differently. That is definitely a welcome edge in an otherwise mundane setting.

Mint Lounge columnist Samar Halarnkar has argued long and convincingly about the need for men to start cooking at home. The other side of that argument is that more and more women need to enter the pro kitchen.

As an Executive Chef, I do not go out there and scout for women cooks but if there’s an applicant with potential and the requisite experience, she deserves a place in our kitchen. We do not look to run a kitchen of women, just one where they feel equal.

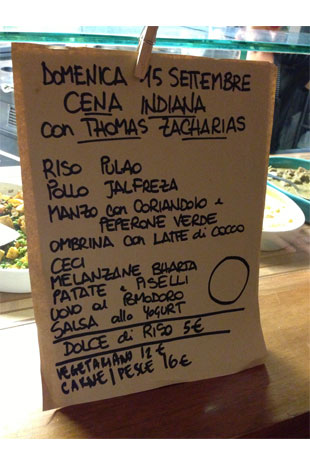

Thomas Zacharias’ inspiration to become a chef came both from his grandmother who gave him his first culinary lessons in Kerala, and his mother who constantly pushes him to do better. He now dons the clogs of Executive Chef at The Bombay Canteen, and looks forward to a world with many, many more women chefs.